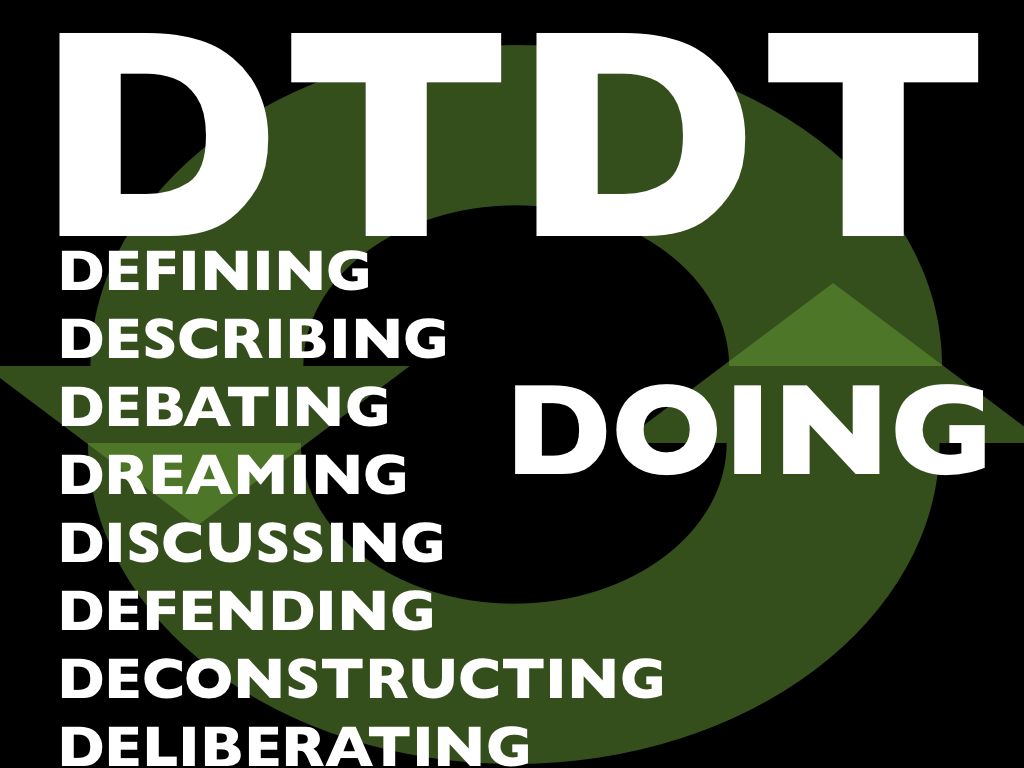

A long time ago, in certain communities of practice in the “user experience” family of practices, an acronym was coined: “DTDT” aka “Defining the Damned Thing”.

For good or ill, it’s been used for years now like a flag on the play in a football game. A discussion gets underway, whether heated or not, and suddenly someone says “hey can we stop defining the damned thing? I have work to do here, and you’re cluttering my [inbox / Twitter feed / ear drums / whatever …]”

Sometimes it rightly has reset a conversation that has gone well off the rails, and that’s fine. But more often, I’ve seen it used to shut down conversations that are actually very healthy, thriving and … necessary.

Why necessary? Because conversation *about* the practice is a healthy, necessary part of being a practitioner, and being in a community of other practitioners. It’s part of maturing a practice into a discipline, and getting beyond merely doing work, and on to being self-aware about how and why you do it.

It used to be that people weren’t supposed to talk about sex either. That tended to result in lots of unhappy, closeted people in unfulfilling relationships and unfulfilled desires. Eventually we learned that talking about sex made sex better. Any healthy 21st century couple needs to have these conversations — what’s sex for? how do you see sex and how is that different from how I see it? Stuff like that. Why do people tend to avoid it? Because it makes them uncomfortable … but discomfort is no reason to shun a healthy conversation.

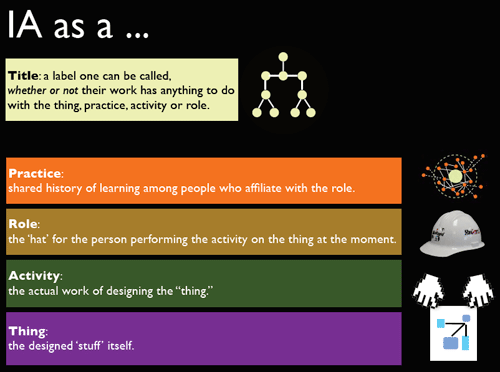

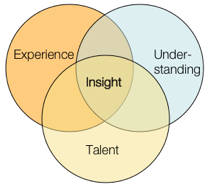

The same goes for design or any other practice; more often than not, what people in these conversations are trying to do is develop a shared understanding of their practice, developing their professional identities, and challenging each other to see different points of view — some of which may seem mutually exclusive, but turn out to be mutually beneficial, or even interdependent.

I’ll grant that these discussions often have more noise than signal, but that’s the price you pay to get the signal. I’ll also grant that actually “defining” a practice is largely a red herring — a thriving practice continues to evolve and discover new things about itself. Even if a conversation starts out about clean, clinical definition, it doesn’t take long before lots of other more useful (but muddier, messier) stuff is getting sorted out.

It’s ironic to me that so many people in the “UX family” of practitioner communities utterly lionize “Great Figures” of design who are largely known for what they *wrote* and *said* about design as much as for the things they made, and then turn to their peers and demand they stop talking about what their practice means, and just post more pat advice, templates or tutorials.

A while back I was doing a presentation on what neuroscience is teaching us about being designers — how our heads work when we’re making design decisions, trying to be creative, and the rest. And one of the things I learned was the importance of metacognition — the ability to think about thinking. I know people who refuse to do such a thing — they just want to jump in and ACT. But more often than not, they don’t grow, they don’t learn. They just keep doing what they’re used to, usually to the detriment of themselves and the people around them. Do you want to be one of those people? Probably not.

So, enough already. It’s time we defend the D. Next time you hear someone pipe up and say “hey [eyeroll] can we stop the DTDT already?” kindly remind them that mature communities of practice discuss, dream, debate, deliberate, deconstruct and the rest … because ultimately it helps us get better, deeper and stronger at the Doing.

I don’t have much to say about this, I just want to see if I can inject a meme in the bloodstream, so to speak.

I don’t have much to say about this, I just want to see if I can inject a meme in the bloodstream, so to speak.