If you’ve ever seen Stanley Kubrick’s movie “Paths of Glory,” it’s a brutal illustration of the distinction between “ideas” and “ideology.”

Kirk Douglas’s character (Colonel Dax) is coming to the “strategy table” after leading his men in the first-hand experience of the trenches. Based on his observations from open-minded, first-hand experience of his troops on the ground, he has ideas about what should and shouldn’t be done strategically. But the strategists, basing their decisions on ideology, force him to lead his soldiers to make a completely suicidal attack: an attack that makes no sense based on what one can plainly see “on the ground.” In this movie, the Strategy Table is ideologically driven; Dax is driven by ideas shaped, and changed, by first-hand experience.

Kirk Douglas’s character (Colonel Dax) is coming to the “strategy table” after leading his men in the first-hand experience of the trenches. Based on his observations from open-minded, first-hand experience of his troops on the ground, he has ideas about what should and shouldn’t be done strategically. But the strategists, basing their decisions on ideology, force him to lead his soldiers to make a completely suicidal attack: an attack that makes no sense based on what one can plainly see “on the ground.” In this movie, the Strategy Table is ideologically driven; Dax is driven by ideas shaped, and changed, by first-hand experience.

In my last post, Austin Govella commented with some terrific questions that made me think a lot harder about what I was getting at. Austin asked: “Is ‘design doing’ the practice of all design practitioners? Can you be a design practitioner whose practice consists of ideology and abstractions?” And it made me realize I hadn’t fully thought through the distinction. But it’s a powerful distinction to make.

In design practice, ideas are the imaginative constructs we generate as we try to solve concrete problems. Ideas are fluid, malleable, and affected by dialectic. They’re raw material for making into newer, better ideas.

Ideology is nearly the opposite. Ideology already has the questions answered. Ideology is orthodoxy, dogma, received doctrine. It comes from “the gods” — and it’s generally a cop-out. We see it in business all the time, where people make decisions based on assumed doctrine, partly because doing so means that if something goes wrong, you can always say “but that’s what the doctrine said I should do.” It kills innovation, because it plays to our fears of risking failure. And it plays to our tendency to believe in hierarchies, and that the top dog knows what’s best just because he’s the top dog.

Let me be clear: I don’t want to paint designers as saints and business leaders as soulless ideologues. That would, ironically, be making the mistake I’m saying we have to avoid! We are all human, and we’ve all made decisions based on dogma and personal ambition at some point. So, we have to be careful of seeing ourselves as the “in the trenches hero” fighting “the man.” There are plenty of business leaders who strive to shake their ideologies, and plenty of designers who ignore what’s in front of them to charge ahead based on ideology and pure stubbornness.

I also realize that ideology and ideas overlap a good deal — that strategy isn’t always based in dogma, and ideas aren’t always grounded in immediate experience. So, when I say “Strategy Table” I only mean that there’s a strong tendency for people to think as ideologues at that level — it’s a cultural issue. But designers are far from immune to ideology. Very far.

In fact, designers have a track record of inventing ideologies and designing from them. But nearly every example of a terribly designed product can be traced to some ideology. Stewart Brand nicely eviscerates design ideology in “How Buildings Learn” — famous architecture based on aesthetic ideologies, but divorced from the grounded experience of the buildings’ inhabitants, results in edifices that people hate to use, living rooms where you can’t relax, atriums everyone avoids. Falling Water is beautiful, and helped architecture re-think a lot of assumptions about how buildings co-exist with landscapes. But Wright’s own assumptions undermined the building’s full potential: for example, it leaks like a sieve (falling water, indeed). Ideology is the enemy of successful design.

Paradoxically, the only thing close to an ideology that really helps design be better is one that forces us to question our ideological assumptions. But that’s not ideology, it’s method, which is more practical. Methods are ways to trick ourselves into getting to better answers than our assumptions would’ve led us to create. (Note, I’m not saying “methodology” — as soon as you put “ology” on something, you’re carving it in marble.)

Jared Spool’s keynote at the IA Summit this year made this very point: ideology leads to things like a TSA employee insisting that you put a single 3oz bottle of shampoo in a plastic bag, because that’s the rule, even though it makes no practical sense.

But the methods and techniques we use when we design for users should never rise to that level of rules & orthodoxy. They’re tools we use when we need them. They’re techniques & tricks we use to shake ourselves out of our assumptions, and see the design problem at hand more objectively. They live at the level of “patterns” rather than “standards.” As Jared illustrated with his stone soup analogy: putting the stone in the soup doesn’t make the soup — it’s a trick to get people to re-frame what they’re doing and get the soup made with real ingredients.

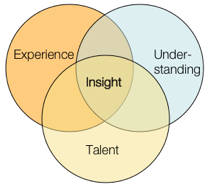

That distinction is at the heart of this “design thinking” stuff people are talking about. But design thinking can’t be codified and made into dogma — then it’s not design thinking anymore. It has to be grounded in *doing* design, which is itself grounded in the messy, trench-level experience of those who use the stuff we make.

Coming to the “Strategy Table,” a big part of our job is to re-frame the problem for the Lords of the Table, and provoke them to see it from a different point of view. And that is a major challenge.

In Paths of Glory, one of the members of the Strategy Table, Paul Mireau, actually comes to the trenches himself. One of the real dramatic tensions of the film is this moment when we can see the situation through Dax’s eyes, but we can tell from Mireau’s whole bearing that he simply does not see the same thing we do. He’s wearing Strategy Goggles (with personal-ambition-tinted lenses!), and ignores what’s in front of his face.

At the “Strategy Table” one of our biggest challenges is somehow getting underneath the assumptions of the strategy-minded, and help them re-think their strategy based on ideas grounded in the real, messy experience of our users. If we try to be strategists who think and work exclusively at a strategic level, we stop being practitioners with our hands in the soil of our work.

But what if we approach this challenge as a design problem? Then we can see the people at the strategy table as “users,” and our message to them as our design. We can observe them, understand their behaviors and mental models, and design a way of collaborating with them that meets their expectations but undoes their assumptions. At the same time, it will help us understand them as well as we try to understand our users, which will allow us to communicate and collaborate better at the table.

Kirk Douglas’s character (Colonel Dax) is coming to the “strategy table” after leading his men in the first-hand experience of the trenches. Based on his observations from open-minded, first-hand experience of his troops on the ground, he has ideas about what should and shouldn’t be done strategically. But the strategists, basing their decisions on ideology, force him to lead his soldiers to make a completely suicidal attack: an attack that makes no sense based on what one can plainly see “on the ground.” In this movie, the Strategy Table is ideologically driven; Dax is driven by ideas shaped, and changed, by first-hand experience.

Kirk Douglas’s character (Colonel Dax) is coming to the “strategy table” after leading his men in the first-hand experience of the trenches. Based on his observations from open-minded, first-hand experience of his troops on the ground, he has ideas about what should and shouldn’t be done strategically. But the strategists, basing their decisions on ideology, force him to lead his soldiers to make a completely suicidal attack: an attack that makes no sense based on what one can plainly see “on the ground.” In this movie, the Strategy Table is ideologically driven; Dax is driven by ideas shaped, and changed, by first-hand experience.